Carl Miller of the Centre for the Analysis of Social Media asserts that “para-political activity is a potent and growing phenomenon”, and if you’ve ever even glanced at social media, you’ll agree. But, note the use of the prefix para-, and his following assertion: “as politics in front of our eyes seems to be business as usual, an earthquake is rumbling under Westminster.” Is it really the case that the likes of Facebook, Twitter and YouTube are galvanising and facilitating a post-postmodern world of political organisation? Will it, or has it already, changed the lives of those who use it to the extent that our future leaders might come to organize and communicate in ways that can’t be racketeered? And in a week in which reports of the Gaza conflict saturate the online mediascape, can it be the case that social media is important and effective enough to in fact make an impact on conflicts like these?

The term ‘social media’ (SM) is often a truncation to describe the now omni-accompanying digital platforms via which we chat blithely to tenuous contacts and acquaintances. The phrase is synonymous specifically with Facebook and Twitter, the profile-based platforms from which the majority of SM users broadcast and receive information, and are largely a deluge of faces, frivolity and thrillingly small animals. SM’s much broader network of tools can be underestimated; the term encompasses a vast amount of ‘Web 2.0’, the modern internet in which user-generated content dominates the landscape and the culture of cyberspace’s constant conveyor belt. YouTube, Instagram and Flickr are all social media tools too, as is Wikipedia, and all online blogs. The collective, collaborative potential of this revolution in communications is well utilized in certain arenas, and taken for granted in others, and the focus on SM as simply an individual’s digital ego-hub is often the source of its dismissal. But there are huge implications in its wider applications of creating, obtaining and transmitting events, visual media and discrete information freely and instantaneously. History need not be entirely written by the winners if the underdogs know their tech.

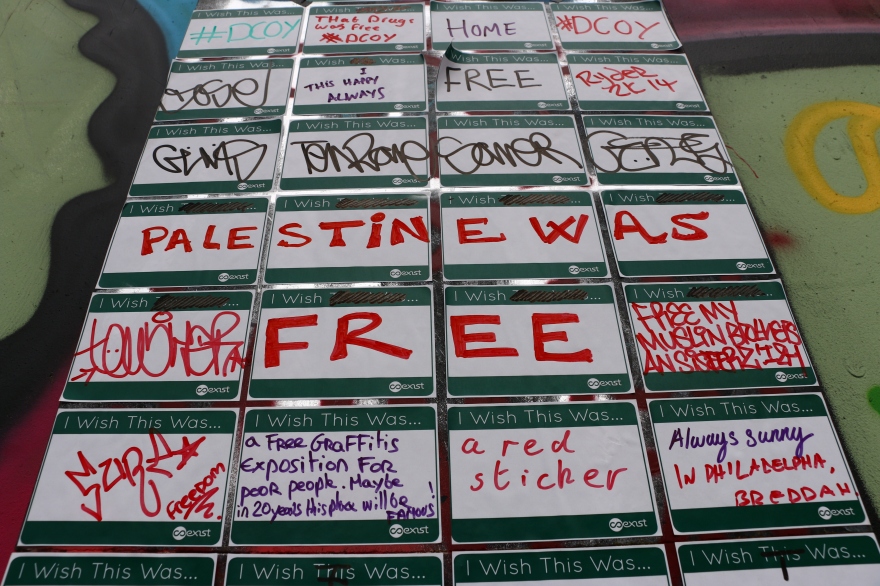

With all this potential, is there concrete value in social media as transformative platforms? Is it easy, or even helpful, to distinguish between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ uses of it (or, in terms of political engagement and activism, ‘effective’ and ‘ineffective’)? Can uploading a photo of your dinner for the umpteenth time ever affect change? What if it’s another inadequate meal supplied by food banks because your parents are out of work, below a link to an article about the rise of the UK’s reliance on them? There are different ways to use SM valuably and effectively, to distribute information, to influence, to make visible, to facilitate understanding. And it seems that social media has the potential to do for awareness of current political crises what television reportage did for awareness of the Vietnam war; then again, the US waged destruction for years in spite of widespread dissent.

Jane Gaines debated a similar question with regard to documentary film in her essay ‘Political mimesis’ – what is it about political and social documentary film that moves people, and when it does, does it actually galvanise them into action? Does exposure to political argument via visual media encourage praxis? Gaines argues that alongside an emotional reaction, the visual representation of violence, struggle and conflict instigates (as all cinema does) a physical, visceral reaction similar to that of pornography; but to arouse the mind, arms, spirit, rather than genitalia. This stimulation can be felt even in the most terrible Hollywood war epics, but when the emphasis is on ‘real’ events, and ones that are occurring now, this bodily response might incite us to act upon what we now ‘know’ as a result of documentary ‘evidence’. This week, videos from Gaza, news reports and opinion pieces have gone viral across SM – not only do they move us emotionally, but hopefully, then, to act.

However, in his column for the New Yorker Malcolm Gladwell famously trashed SM ‘activism’, explaining that the ‘act’ largely ends at the click of a button: “the platforms of social media are built around weak ties. […] There is strength in weak ties, as the sociologist Mark Granovetter has observed. Our acquaintances—not our friends—are our greatest source of new ideas and information. […] But weak ties seldom lead to high-risk activism.” Gladwell points out that SM is a participatory, not motivational, tool that lessens the level of motivation that participation requires – by sharing that video of the boy with his face blown off, you’ve done what you can. You’ve distributed the information, perhaps contributed to others’ awareness; what else can you do?

How can we determine the value of this kind of activity? On one hand, how exactly can you help victims of atrocity other than by making people aware of their fate? Perhaps you share a few more videos, a few more articles. On the other, it’s clear that the definition of ‘help’ here is barely workable; what the children of Gaza needed was real political change years ago. How cynical can we be about our ability to affect the world? Does anyone know which acts will actually change a situation? Clicking the ‘Like’ button? Retweeting? What is it good for – absolutely nothing?

On the other side of the fence is Clay Shirky, who believes that “the fact that barely committed actors cannot click their way to a better world does not mean that committed actors cannot use social media effectively.” While it is true that masses of apathetic, alienated, square-eyed youth in the UK spend vast amounts of time interacting predominantly digitally, their interaction with internet culture and SM can be optimal for an introduction to political awareness, even if not political action, if used with intent. Internet culture, especially ‘geek’ or ‘nerd’ culture, has a strong interest in social justice, and this interest is reflected in SM content and even popular internet culture far more than it is in mainstream popular media. Internet culture is certainly influenced by mainstream culture, but can also act in opposition to it; in order to gain the most out of the power of the horizontally-organised counter cultural cyberspace, you have to want to immerse yourself in learning and acting on your knowledge. The crux of the problem being, therefore, that the majority of our culture and national curriculum distinctly lacks political analysis or awareness in the first place. And it’s not only young people who lack the drive.

It’s an ongoing struggle to encourage people to engage, but more and more communities exist online that encourage us to learn, and act. John and Hank Green, using their hit YouTube channel Vlogbrothers and numerous other SM, have created an online culture with a network of users and fans named ‘nerdfighteria’. [Said fans and users (‘nerdfighters’) are self-proclaimed nerds who fight the perennial scourge of worldsuck to increase awesome.] The Project for Awesome (P4A) is a yearly fundraising drive that the Vlogbrothers run via YouTube, encouraging users to upload videos in support of charities, thereby increasing awareness and encouraging their audiences to donate. For 2013’s P4A they also utilised crowdfunding site Indiegogo, raising $721,696, breaking Indiegogo’s record for the most money raised by a campaign. Together with the YouTube efforts the total raised in 2013 was $869,591.

Popular comic creators who make the most of their hits through social media such as Cracked and CollegeHumor have also used their presence to bring political issues to their audiences. Increasingly, these mainstream humour sites are distributing videos via SM that discuss issues such as gay rights, women’s rights, and net neutrality, for example. While this makes political tension accessible to people who might otherwise choose not to engage, what comes of the access to these videos? Could we justify creating content about the situation in Gaza for a mainstream comedy audience? CollegeHumor’s YouTube channel has 7.5 million subscribers; Reuters, BBC News and Associated Press have less than 1 million combined, reflecting both a creator and audience focus on lighter topics that can be made funny rather than the most urgent of political crises. This disparity here between passively encountering politics in one’s entertainment media, and engaging with active political organizations who are acting IRL illustrates Gladwell’s point nicely.

As far as the dynamic between SM and the mainstream media (MSM) goes, many have hastily hailed SM’s horizontal power structure as a cure-all alternative, while ignoring the complexities of the ever-intensifying relationship between them. Rather than expressing any distaste or worry about SM as a defiance, Martin Niesenholtz of The New York Times notes that SM is “highly complementary to what [they] do”. While SM has the ability to inform where the MSM won’t (rather than can’t), the MSM is also absorbing and incorporating it, and fast. Corporate news isn’t going anywhere quite yet, and until SM provides a direct challenge to it by making itself better organised, it will remain complementary. For example, both CNN and Al Jazeera have established networks of volunteers on the ground in crisis situations to provide news content to them via SM, which is then verified by journalists back at HQ; indeed, Al Jazeera’s network was set up as a direct response to the 08-09 conflict in Gaza. While SM can provide a fighting alternative to the blackouts and corruption we see too frequently from MSM houses, its loose networks suffer from a lack of direction, organisation and verification that provide their own problems. The MSM is quickly learning to pick up that slack while reaping the benefits of horizontally organised groundwork.

Former BBC ‘future media’ executive Nic Newman posited that while Twitter has a significantly smaller audience than Facebook, its users are the real “influencers. […] The audience isn’t on Twitter, but the news is on Twitter.” Jeff Jarvis of the City University of New York noted that political conversations and debates are going on already, and journalists need to realize they are simply a part of this wider discourse, and should focus largely on providing context, debunking, and analysis. Channel 4 News seems to have cottoned on to this with regard to Gaza, creating a web video of significant critique from head reporter Jon Snow. In only a week the video has received around 900,000 views, several times that of any other of Channel 4’s videos that have been live far longer. In 5 minutes, Snow details his direct experience, providing visual evidence, critical context and concise analysis of the situation in Gaza, with a focus on the issue of most urgency: the fatal damage to its children. The length, content and style of the video makes it optimal for informing SM grazers about the situation, and is of course shareable across all SM platforms from YouTube. This is a particularly effective and efficient example of the way this collaboration can be used to influence people, engage them with politics, and pass that influence and engagement on. People want to engage, and when the opportunity appears amongst our shiny distractions, most will take that first step.

Two other videos concerning Gaza that have stood out for me this week are user-generated, and quite different. One, so vile, spurred me to act. I did not watch it, I saw only the thumbnail image. It shows a boy whose entire jaw is missing, ripped away by a bomb, and entering a hospital – to have what done to repair him, I can’t imagine. Stunned, I could not look away. I dipped my eyes to the comments below. The first one simply read

“guy comes in with no bottom jaw. Doctor spends 40 seconds making sure that he films him.. Riiiiiiiight.”

Disturbed by both the image and the blasé, cynical response, I felt sick, powerless; but determined to respond. The following comments were all of shock and disgust, and one admonished the sharer for posting it in the first place. Some questioned its authenticity; all legitimate concerns. How many other people were moved to act, share, write, boycott Israeli goods, pen a letter to the government…I do not know, and I suspect very few. I wish it had never happened; in lieu of that, I will engage with it.

The other video was of the previous day’s protests in Brighton and made by a filmmaking colleague, Lee Salter; a short observational reportage-style video in which members of the march were interviewed and the subject analysed. They spoke of boycotting Israel-trading outlets, of why they choose to march, of their frustration at the snails pace of change. The video is titled ‘Gaza to Brighton – things that we can do for Gaza’; one that encourages engagement and sharing, to consider actions such as marching and boycotting, to make noise and demand change, and make visible the people who are enacting this resistance already and how we might join them. It might not feel like much, but it’s often all people feel they can do, disenfranchised and confused as they are.

Gladwell makes a damning but noteworthy assertion about the power structures of internet networks, social and political. “Unlike hierarchies, with their rules and procedures, networks aren’t controlled by a single central authority. Decisions are made through consensus, and the ties that bind people to the group are loose. How do you make difficult choices about tactics or strategy or philosophical direction when everyone has an equal say?” Collective organizations can be successful when they have solid aims. If unions got distracted by putting cats in mugs and making gifs of them, would we be surprised when the strikes never happened? The Internet does not have solid aims, because it represents a vast number of people on the globe, a huge number of the whom are are ill-informed, unhappy, bored and understandably disillusioned. To ensure the productive and effective use of SM by the user, the audience, the masses, we need to understand what it is good for, and what it’s limitations are. Clay Shirky, in part, finds agreement with Gladwell here: “social media tools are not a replacement for real-world action but a way to coordinate it.”

The dissemination of information and ideas is only the first step for political engagement. For the majority of SM users, especially the slacktivists who think they’re affecting change by clicking a button, it’s the last. Direct activism and action can be suggested, encouraged and introduced by SM, but nothing will replace work done and demands made on the ground. Unfortunately, radical action (and even democratic action) are silently discouraged by the structure of our lifestyles, our 9 to 5 hours that could be better distributed, our entertainment-saturated landscape, our addictions encouraged by advertising, and illiteracy concerning power. Again, Gladwell denounces SM for making “it easier for activists to express themselves, and harder for that expression to have any impact. The instruments of social media are well suited to making the existing social order more efficient.”

It is easier than ever to type in a keyword about human trafficking, Gaza, environmental degradation and corporate corruption and instantly find reams of articles, twitter accounts and discussion boards providing the networks, connections and information to get started, but the audience needs to be searching in the first place. Education reform, parental guidance, and commitment to engagement in conversation are absolutely essential. Shirky’s assertion that “access to information is far less important, politically, than access to conversation” is astute; we must maintain the conversations and encouragement with each other (IRL) that may make or break our futures.